1.

For the final proposal, please provide your organization's comments on the export, load and wheeling priorities proposal:

CPUC staff recognizes that California is interconnected to the entire Western electric grid and, as such, must work with neighboring balancing authorities and must treat in state and out of state entities fairly when it comes to access to the bulk transmission grid. We appreciate the challenges the CAISO faces in ensuring equal access to entities that are either exporting from California, or wheeling through California, while also meeting its obligations to provide reliable service to the load within the balancing authority. However, we are concerned that in some circumstances the proposals will unnecessarily increase the risks to California load.

CPUC staff is concerned that the existing and proposed rules prioritize exports and wheels over native load and, if allowed to continue, will seriously jeopardize reliability in the state and undermine the resource adequacy and transmission planning processes. To this end, CPUC staff agrees with the CAISO, the IOUs and other parties that ultimately a durable solution will need to be developed and ask the CAISO to make further development of these rules a priority.

CPUC staff is particularly concerned about this issue because of the uncertainty of the magnitude of wheeling transactions. If wheel throughs are limited to a few hundred MWs, the challenge would be manageable this coming summer, but staff is concerned that wheeling transactions could approach thousands of MWs. For example, during the 2020 August stressed system conditions, the CAISO system was exported 4,000 - 5,000 MW, primarily to the Southwest. CPUC staff agrees that that recent actions by the CAISO have foreclosed this risk going forward but, we are concerned that these export transactions during tight system conditions will migrate to wheeling transactions. CPUC staff’s concern is further exacerbated by the fact that entities wheeling through the state do not need to reserve this space in advance, nor pay for the entire month or schedule every day. Thus, there is little visibility regarding the magnitude of the issue and little opportunity to plan for and address it, should it arise.

Further, given that prices are now considerably higher at Palo Verde (in the south) than at Malin (in the north), CPUC staff expects that this could further increase wheeling transactions and, as a result, displace California resource adequacy import contracts for energy and the movement of energy from northern California (where there is typically excess generation) across the constrained transmission system to southern California. In other words, CPUC staff is concerned that the use of the California transmission system to move power from the Northwest to the Southwest could use valuable transmission space and crowd out use by Californians themselves and thereby jeopardize reliability this coming summer.

Finally, CPUC staff is concerned that any number of entities could indicate that they have signed a contract to obtain PT wheeling status to reserve space, but that these contracts could be provisional or have no penalty provisions, because there are no clear requirements or upfront costs. Thus, it seems possible that CAISO could give PT wheeling status to many entities for large quantities of MWs, which may or may not materialize in the operational space and, if they do, would be given priority over load in all instances, except when there is load shedding in which case they would be given a pro rata allocation, to the detriment of reliability for California customers.[1]

Thus, for situational awareness, and because the primary purpose of this stakeholder process is to prepare for this summer, CPUC staff strongly encourages CAISO to request that parties provide information on the wheeling transactions that are signed as of the date of the FERC filing as soon as possible to allow for coordinated planning for this coming summer.

The following sections discuss CPUC staff concerns in further detail.

CPUC Staff Is Concerned that Prioritizing PT and LTP Wheels Over Resource Adequacy Import Contracts at All Times, Except When there is Unserved Load and in that Case Only Allocating Pro Rata Based on Available Bids, Could Jeopardize Reliability this Summer

By way of background, CPUC staff notes that the evolution of this proposal throughout the stakeholder process has moved from prioritizing load over wheeling transactions to the current proposal which now prioritizes wheeling transactions (both PT wheels and LPT wheels) over load, except when there might be a load shedding event, in which case it allocates the transmission system on a pro rata basis. This can be seen in a couple of examples from the draft final proposal and the final proposal:

The following compares the draft final proposal and final proposal with respect to RA imports bidding less than $0 and wheeling transactions (emphasis added).

Integrated Forward Market

- Draft Proposal: If an import submits a bid below $0/MWh (for example -$5) and it is needed to meet self-scheduled load, the cost of not meeting load is $1455. The cost of not meeting the wheel is $1450. The import will clear IFM and the wheel will not.

- Final Proposal. If an import submits a bid below $0/MWh (for example -$5) and it is needed to meet self-scheduled load, the cost of not meeting load is $1455. The cost of not meeting the PT wheel is $1850. The cost of not meeting the LPT wheel is $1150. The PT wheel will clear IFM before the import. The import will clear IFM before the LPT wheel.

Residual Unit Commitment Process

- Draft Proposal. If an RA import that did not clear IFM is needed to meet the CAISO load forecast, the cost of not meeting load is $1600. The cost of not meeting the wheel is $1600. The import or the wheel will clear RUC.

- Final Proposal. If an RA import that did not clear IFM is needed to meet the CAISO load forecast, the cost of not meeting load is $1600. The cost of not meeting the PT wheel is $2250. The cost of not meeting the LPT is $1350. The PT wheel will clear RUC before the import. The import will clear RUC before the LPT wheel.

Hour Ahead Scheduling Process

- Draft Proposal. If a real-time import that economically bids less than $0/MWh (such as -$10) is needed to meet the CAISO load forecast, the cost of not meeting load is $1460. The cost of the wheel is $1450. Load will be served before any RUC or RT wheel.

- Final Proposal. If a real-time import that economically bids less than $300/MWh (such as $200) is needed to meet the CAISO load forecast, the cost of not meeting load is $1250. The cost of not meeting the RUC PT wheel is $2200. The cost of not meeting a real-time PT wheel is $1850. The cost of not meeting the RUC LPT wheel is $1150. The cost of not meeting the real-time LPT wheel is $1050. The RUC or RT wheel will be served before CAISO load. The RUC wheels will clear HASP before real-time PT wheels. Real-time PT wheels will clear HASP before load. Load will clear HASP before RUC LPT wheels. RUC LPT wheels will clear HASP before real-time LPT wheels.

As this demonstrates, wheels are given priority over load in most circumstances.

We note that CAISO proposes a post-HASP adjustment process, which will allocate import capacity between wheels and load on a pro-rata basis, but this would be done only if CAISO were at the point of cutting load, not before, and this only helps to the extent that there are imports available in the real-time to serve load. For example, assuming import capability of 4,000 MW with 4,000 MW of RA imports and 4,000 MW of wheels, load would be cut by 2,000 MW and wheels would be cut by the same amount. This does not seem consistent with the magnitude of the payments made by load and wheels.

Staff’s additional concerns with the final proposal are as follows:

- The examples above address what happens when RA imports are needed to serve load, but in the case when the RA imports are not technically needed to serve load, CAISO’s proposal prioritizes both PT wheels and LPT wheels over resource adequacy contracts for import energy in all instances. Thus, if a load serving entity has procured an energy import contract to meet its RA requirements and serve its load or to ensure reliability, as was done in response to the CPUC reliability OIR, then if there are wheeling transactions, these RA import energy contract would be crowded out. This is an issue because these energy contracts serve as a hedge and are meant to ensure reliability in 1-in-2 conditions.

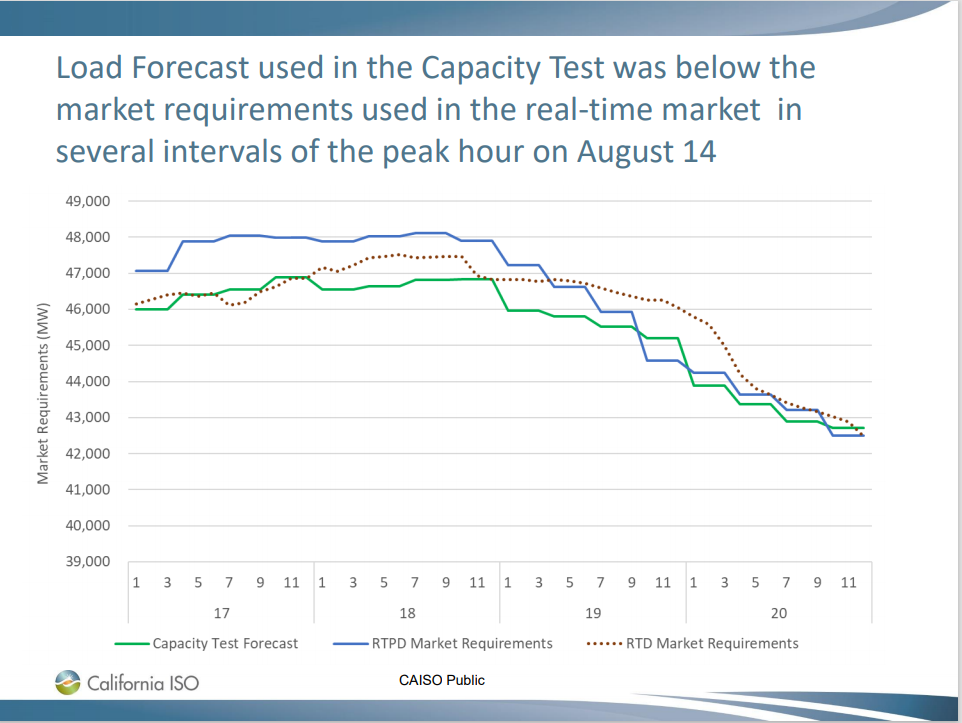

- Further, if RA imports do not clear in the IFM, they have no further obligation in the real-time. CAISO has indicated that it will commit RA imports in the RUC process if there are infeasibilities, but what happens if there are no infeasibilities in the RUC process, but those RA imports might have been needed to serve load (if the load forecast were higher in the real-time than in the RUC process)? It is CPUC staff’s understanding that CAISO will bias the RUC process to ensure that load uncertainty is covered. Nonetheless, even with this bias in the RUC, we remain concerned that CAISO could be left with insufficient RA resources in the real-time because RUC fails to commit sufficient resources, as was discussed by CAISO during its resource sufficiency meeting (see figure below, which demonstrates that load was higher than load forecast in crucial hours last summer).

- In addition, CPUC staff is concerned that PT wheels can come in during the real-time process and adversely affect the post-HASP adjustment process. For example, assume there is a 300 MW import limit, and CAISO clears 200 MWs of RA import bids and 100 MW of PT wheels and the RUC process is feasible. Assume that due to load forecast changes, the HASP process clears the same amount, but now there are 100 MW of RUC PT wheels and 100 MW of RT PT wheels, in this case, the post-HASP process allocation process will allocate more to wheeling transactions. Which schedule does the operator use?

- Also, should CAISO issue a CPM for an import resource to address reliability concerns, this resource is not guaranteed to flow and could be crowded out by wheeling transactions. Similar to other imports, the CPM resource would not have a real-time must-offer obligation if it is not picked up in the day-ahead process. This process calls into question what reliability benefit import CPM resources (and in fact all imports) provide when they are all prioritized below wheels and at best, during tight system conditions, only a fraction of the RA import and CPM transactions will flow.

- It would also be helpful if CAISO could clarify whether a variable energy resource can support a PT wheeling transaction.

Finally, as we have stated previously, CPUC staff supports prioritizing high priority exports and load above wheeling transactions, consistent with CAISO’s initial proposal regarding wheeling transactions, as it is consistent with FERC’s open access tariff, with open access tariffs of other entities, and with CAISO’s existing tariff regarding import allocation rights.

Regarding FERC’s Order 888, FERC stated that, “We conclude that public utilities may reserve existing transmission capacity needed for native load growth and network transmission customer load growth reasonably forecasted within the utility's current planning horizon. However, any capacity that a public utility reserves for future growth, but is not currently needed, must be posted on the OASIS and made available to others through the capacity reassignment requirements, until such time as it is actually needed and used.”

Further, other entities, such as BPA, provide either non-firm or firm point-to-point transmission service and only firm point-to-point service is given equal priority to native load, and firm point-to-point service is only granted if it does not impair the reliability of service to Native Load Customers…”

13.2(v) Firm Point-To-Point Transmission Service will always have a reservation priority over Non-Firm Point-To-Point Transmission Service under the Tariff. All Long-Term Firm Point-To-Point Transmission Service will have equal reservation priority with Native Load Customers and Network Customers. Reservation priorities for existing firm service customers are provided in Section 2.2.

13.5 In cases where the Transmission Provider determines that the Transmission System is not capable of providing Firm Point-To-Point Transmission Service without (1) degrading or impairing the reliability of service to Native Load Customers, Network Customers and other Transmission Customers taking Firm Point-To-Point Transmission Service, or (2) interfering with the Transmission Provider's ability to meet prior firm contractual commitments to others, the Transmission Provider will be obligated to expand or upgrade its Transmission System pursuant to the terms of Section 15.4. The Transmission Customer must agree to compensate the Transmission Provider for any necessary transmission facility additions pursuant to the terms of Section 27. (Emphasis added.)

In addition, CAISO’s tariff includes provisions regarding import allocation rights (see section 40.4.6.2), which are allocated to internal load serving entities to pair with resource adequacy resources to ensure the reliable operation of the grid:

For Resource Adequacy Plans covering any period after December 31, 2007, total Available Import Capability will be assigned on an annual basis for a one-year term to Scheduling Coordinators representing Load Serving Entities serving Load in the CAISO. (Emphasis added.)

CPUC Staff Is Concerned that Allowing Variable Energy Resources to Support PT (High Priority) Firm Exports Could Jeopardize Reliability this Summer

In its March 19th Final Proposal, CAISO proposes to allow variable resources to support PT exports. CPUC staff is concerned that this could jeopardize reliability if the CAISO system (e.g., resource adequacy resources) are called upon to support PT exports that do not show up in real-time. For example, assume that a load serving entity outside of the CAISO system (LSE A) signs a contract for a 1000 MW (nameplate) wind resource within the CAISO balancing authority. LSE A then self-schedules this wind resource as a PT export in a peak, critical hour (e.g., similar to August 14, 2020 at 6 pm) at 250 MW, but then it produces only 100 MW or 0 MW. In either case, under CAISO’s current proposal, it would export the 250 MW, even though the resource was only producing 100 MW or 0 MW.

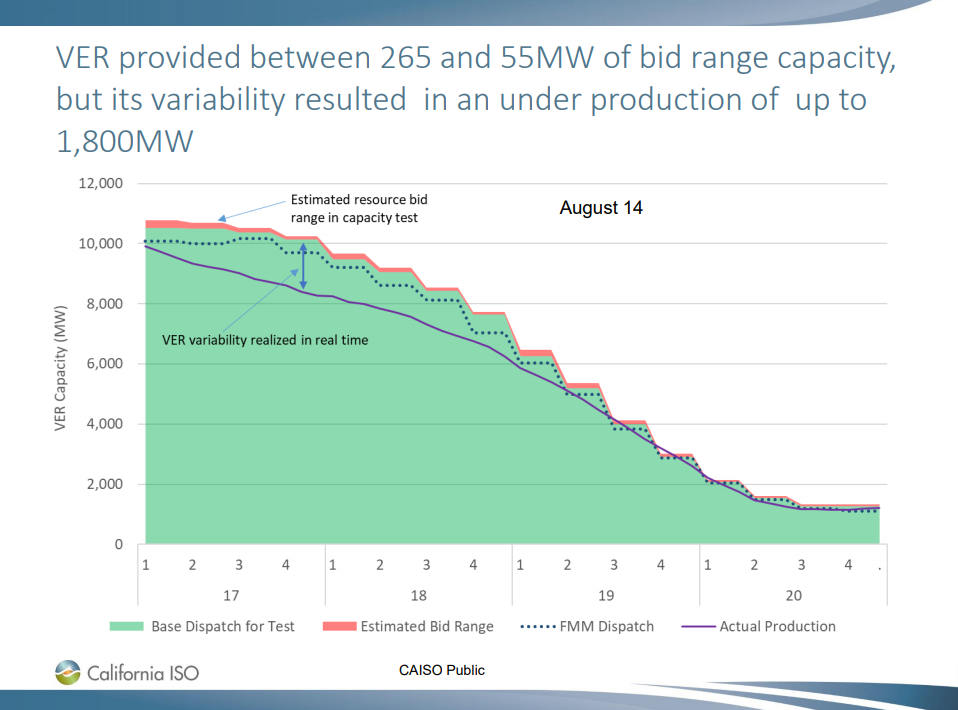

CPUC staff are concerned that such a scenario outlined above could occur for the following reasons. First, in its presentation on resource sufficiency on March 30, 2021, CAISO indicated that the forecasts for variable resources are often too high (see CAISO figure below) and that this can occur during critical peak periods. As this figure demonstrates, the FMM dispatches on August 17th and August 18th (and presumably forecasts as well) were up to 1,800 MW above actual production in real-time. Second, CPUC staff has reviewed the PT exports during the August events and there were variable resources that supported PT exports and the self-scheduled quantities in one hour, for example, exceeded actual production by 40 percent. Thus, this is not a theoretical issue.

Given that CAISO could then be exporting a resource that is not producing energy or producing less energy than scheduled out of the system (and, thus, leaning on the CAISO system), CPUC staff does not understand how this proposal supports or increases summer reliability and, in fact, is concerned that this proposal could undermine reliability this coming summer.

Therefore, CPUC staff recommends that the PT export quantity be tied to the actual generation of the facility. CAISO has indicated that this is not possible for this summer, in which case, CPUC staff recommends that CAISO return to its previous proposal, which would only allow PT exports to be supported by resources that can support an hourly block schedule, which would exclude variable resources. This is consistent with treatment in other balancing authorities, such as Idaho Power, which only allow exports to the extent that the underlying resource is generating.[2] Further, other balancing authorities require variable resources to be firmed and shaped to fit into hourly block schedules, which is expensive – CAISO is not requiring that here. Finally, given the importance that CAISO and other parties have placed on not allowing one system to lean on another system, it is incongruous to turn a blind eye to this type of leaning here.

CAISO appears to be arguing that restricting the export level to the lowest of the 15-minute schedule would prevent leaning.[3] However, CAISO’s figure above demonstrates that the FMM dispatch (and presumably the forecast underlying it), can fall short of actual production. Thus, this proposal does not address concerns about leaning (and exporting power that is not being generated). Further, CAISO proposes no consequence for the LSE or resource if the forecast falls short -- forecasts are always wrong and there appear to be no consequence if the forecast does not match actual production. On the other hand, exporting power to support PT exports that are under-generating could jeopardize reliability – a real and tangible consequence that this stakeholder process was meant to address.

In addition, CPUC staff has some concerns about the penalty prices for PT exports. Given that the penalty parameters for RUC PT exports and real-time (RT) PT exports are the same, this would appear to set up a reliability concern if the exports only show up in the real-time and are not taken into account when determining the resources needed to meet load in the RUC process. For example, assume that there is a 1000 MW resource in California that bids into the CAISO market and is dispatched, and thus CAISO does not commit a long-start resource, but then that resource identifies itself as a PT export in the HASP process (where it gets priority equal to load) – this would appear to set up the system for potential uncertainty and instability and would seem to argue for adjusting the RUC process to ensure that sufficient resources are committed to serve load. As a result, CPUC staff recommends that PT exports be given equal priority to load only if they are identified in the day-ahead and that PT exports should not be allowed to materialize in the HASP process and be given equal priority to load and potentially threaten the reliability of the grid. This would be consistent with the current process, where real-time exports are given lower priority than day-ahead exports.

Further, while the final proposal states that PT exports will not be prioritized above load (as in the draft final proposal), there is no discussion regarding what this means in practice. In the appendix, CAISO indicates that the penalty parameters for PT RUC and RT PT exports are the same as load and in a note to Table 2, indicates that “The scheduling priorities are DAPT = RTPT = Load/Demand > DALPT > RTLPT.” Some questions that arise include the following:

- Does CAISO know how this will work in practice and, if so, can they provide this information to stakeholders? Is it possible that loss factors could result in only cuts to load and no cuts to PT exports and/or what other factors would determine the outcomes under stressed system conditions?

- Will there be any post-HASP adjustment to cut load and PT exports on a pro rata basis? What would pro rata cut look like if there are 1000 MW of PT exports and 45,000 MW of load? If there is no post-HASP process, how will CAISO be allocating cuts to PT exports and load in the event that there are insufficient resources to support both?

Because these questions are not discussed in the final proposal and were not discussed on the stakeholder call, CPUC staff is concerned that while the final proposal states that PT exports and load have equal priorities, that in practice, PT exports will be prioritized over load. This is even more concerning if this occurs when the supporting resource is under-generating or not generating compared to its forecast and/or schedule.

Finally, CAISO states that imports cannot support PT exports (“Exporters cannot designate an import to support a PT export. These transactions can bid properly as a self-schedule wheel through,” p. 19). It would be helpful if CAISO could clarify that this this provision applies equally to pseudo-tied and dynamically scheduled imports. If CAISO does not clarify this is the case, a variable energy resource that is pseudo-tied into CAISO could then support a PT export and, in this way, turn a variable import resource into a firm export resource merely by moving it across the CAISO system, again to the detriment of load under stressed system conditions (which would need to support any under generation of this PT export).

Errors in the CAISO’s Final Proposal Should be Corrected

CPUC staff believe that there are a few errors in the final proposal that should be fixed, to avoid any confusion.

- First, in the final proposal, CAISO states that, “The CAISO is creating a new Master File flag that the resource scheduling coordinator should select if it is unable to attest to the rules above, which will prevent the resource by being designated by a scheduling coordinator of an export.” However, CAISO clarified in the last stakeholder call that the Master File flag will default to “no” and only if the resource can support a PT export would the scheduling coordinator select that it is able to attest that it can support a PT export. Thus, this sentence should be updated to read, “The CAISO is creating a new Master File flag that the resource scheduling coordinator should select if it is

unable to attest to the rules above, which will only allow those resources that have attested that they meet these rules to be used to support a PT export.prevent the resource by being designated by a scheduling coordinator of an export.” CPUC staff agrees with CAISO that this formulation should be applied as there are thousands of resources and only potentially a handful of resources supporting PT exports. Thus, it makes sense that only those resources able to support PT exports should need to modify the Masterfile, as opposed to scheduling coordinators for all resources attesting that they do not meet the criteria, which would be burdensome, create confusion, and undermine reliability if the flags were all set to allow PT exports for thousands of resources by default.

- Second, on p. 44, in the IFM example, CPUC staff believes that the PT wheel figure of $1450 (highlighted below) should be set to $1850:

“If an import submits a bid above $300/MWh (for example $310) and it is needed to meet self scheduled load, the cost of not meeting load is $1140. The cost of not meeting the PT wheel is $1450. The cost of not meeting the LPT wheel is $1150. The PT wheel will clear IFM before the LPT wheel. The LPT wheel will clear IFM before the import.”

- Third, on p. 45, in the RUC example, CPUC staff believes that the PT wheel figure of $1600 (highlighted below) should be set at $2250.

“If an IFM-cleared non-RA import that self-scheduled in IFM is needed to meet the CAISO load forecast, the cost of not meeting load is $2250. The cost of not meeting the PT wheel is $1600. The cost of not meeting the LPT wheel is $1350. The import or the PT wheel will clear RUC, but both will clear before an LPT wheel.”

[1] California customers pay $2.6 billion for the high voltage transmission system each year and wheeling transactions pay $13/MWh, which amounts to $65,000 for 5,000 MW for 1 hour or $3.9 million for 60 hours, assuming that wheeling transactions are scheduled only during stressed system conditions. By contrast, if wheeling transactions were required to pay to reserve the system for an entire month, which is not required under this proposal, the charge for 5,000 MW would be $47 million.

[2] "One exception is that if, in real time, the third-party generator supporting an export is not generating (e.g., due to forced outage) or is under-generating compared to its transmission exporting schedule, the balancing authority area may curtail the schedules to a level commensurate with generator production to avoid exacerbating the energy shortage and associated imbalance." CAISO's Final Proposal, p. 13.

[3] “A variable energy resource not contracted to meet resource adequacy can meet this attestation if the forecast of the resource can support the export quantity in all 15-minute intervals. For example, assume the forecast for interval 1 is 50MW, interval 2 is 45MW, interval 3 is 55MW and interval 4 is 60MW, this resource could support a 45MW PT export.” CAISO Final Proposal, p. 19.